In this ‘Behind the Paper’ blog post, author Louise Cheynel – a Postdoc at Lyon 1 University, France – shines a light on the impacts of nocturnal light pollution on toad health. Louise discusses the implications of her research, the logistics behind an intensive 9-night field campaign, and what she’s learned from her study species.

About the paper

Nocturnal light pollution is the fastest-growing pollution worldwide: 85% of the European territory is now affected by it! While scientists and naturalists quickly realized that it affects animal behaviour (activity, migration, reproduction), very little is known about its effects on wildlife health. Studies conducted in the lab suggest that it can have negative effects on immunity. The problem is: we do know now that results found in lab conditions are not always very representative of what really happen in nature.

Our aim was thus to test if the exposure to nocturnal light pollution affect negatively the health of a frequently encountered amphibian of wetlands, the common toad. Common toads, like many other amphibians, are nocturnal and thus particularly sensitive to light pollution. Novelty was to test this in completely natural conditions, in its natural habitat, rather than in the lab or with experimental settings as it has previously been done.

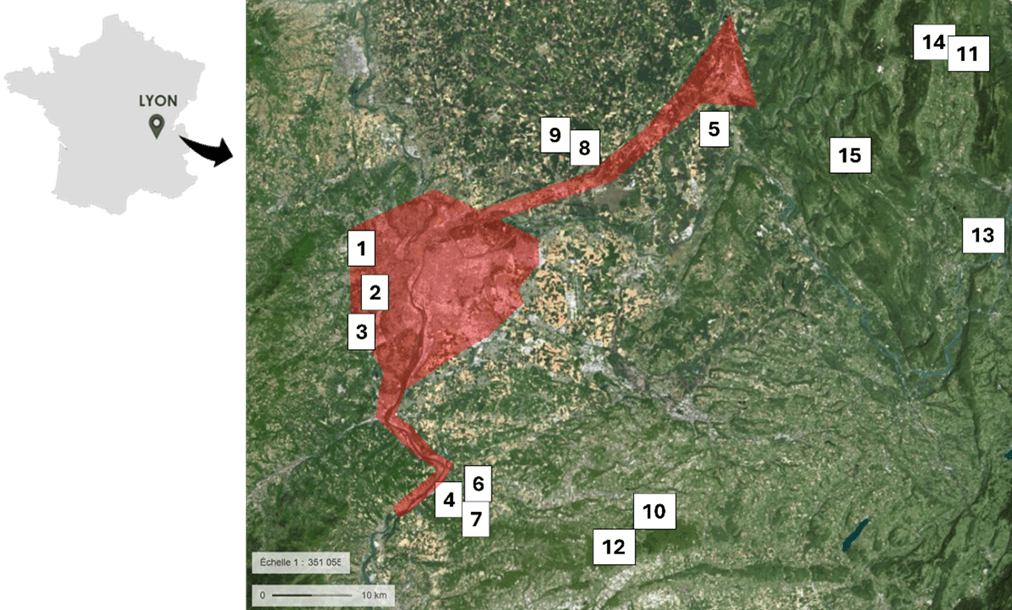

When comparing toads from 15 natural sites on a gradient of exposure to light pollution, we found that toads living in darkest sites were much bigger than toads living exposed to high levels of light pollution. The contrast was so striking that we could see it with the naked eye on the field! This was a very interesting result because it matches previous behavioural experiments conducted in our lab, where toads show a dramatic decrease of their activity and hunting capacities when exposed to light (mainly because of their dark-adapted eyes) and thus probably of their feeding activity.

We also found differences in their immunity but the results were different from our predictions. Effects on immunity were also rather due to global urbanisation than to light pollution only. This proves that the effects of light pollution on wildlife are likely to be different than those reported in lab studies and that we need more research in the field.

Finally, our study has implications in terms of conservation, as amphibians are a threatened taxa worldwide, it is important to understand how they are affected by a very common anthropogenic pollution.

About the research

This work has been made possible by an intense fieldwork campaign!

Common toads are a species living in forests and migrate in early spring to reproduce in the same pond each year. This migration period, that happens at night in February-March, only lasts one or two weeks : they are called ‘explosive breeders’. As this is this only time of the year where we can have access to animals, we have to be ready and not miss the event! For the study presented here, all sampling realized on the 150 toads from the 15 different sites have thus been realized in only 9 consecutive nights. With the cold in early March, the long driving between sites and the time needed to sample each animal* – this represented very long hours of nocturnal work, but we were really happy to be able to collect all our data in such a short time!

* Amphibians are protected species in France – several permits were obtained to do this study and all toads were quickly released on site after cautious biological sampling, all in perfect condition.

About the author(s)

I’m a Marie Curie Postdoc Fellow at the LEHNA (Natural and Anthropized Hydrosystems Ecology Laboratory) research unit in Lyon 1 University, CNRS, France. Like most ecologists, I have been passionate about animals since my childhood. In the last 10 years, my work has been focusing on what drives health, immunity and microbiome of wild animals in nature, and the consequences on their life-history traits. I have been working on very different animal models: tree frogs, roe deer, a subterranean crustacean, wild house mice and now toads – I have learned so much from all of them. Being a researcher in ecology is a fascinating job that I love, it is a blessing to be able to work with wild animals in nature, but I do regret the difficulty of my generation to secure academic positions in France, the lack of funding for ecological questions, but also that our work in ecology does not translate enough in our countries’ politics. I hope that we, scientists, ecologists, naturalists, nature lovers, will organize ourselves more collectively in the future to be more present in the public debate and influence policies more.