Renato Morais of James Cook University presents his 2020 Haldane Prize shortlisted research ‘Severe coral loss shifts energetic dynamics on a coral reef‘ and talks about his PhD experience where he learned that catastrophe doesn’t mean that all is lost.

If I was asked to provide advice for someone starting a (PhD) project in Ecology, it would be don’t get emotionally attached to your project. Research plans change, but more often than not they will make your research even more interesting.

In early 2016 I was finalising my enrolment in a PhD in Marine Ecology half-world away from home – so lots of excitement and apprehension – when I got a call from my prospective supervisor. ‘Look mate, the reef has been hit by a heatwave, corals bleached, many of them cooked to death’ (NB: bleaching is a physiological response of corals to exceedingly hot waters in which symbiotic algae are expelled, often leading to coral starvation and mortality).

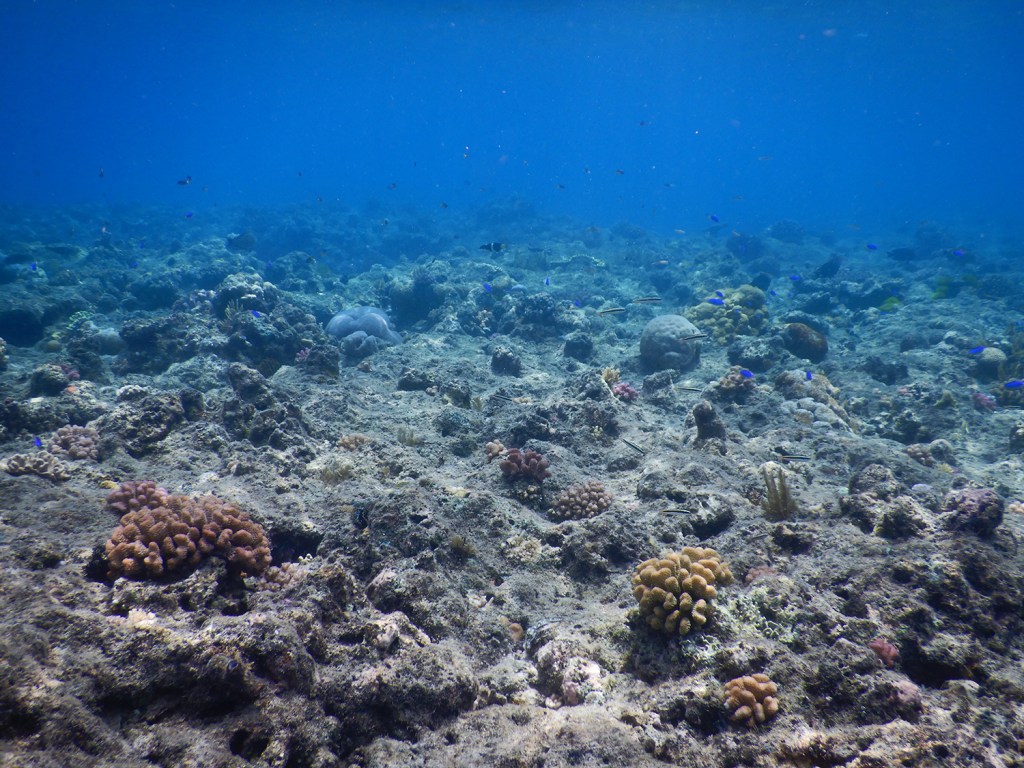

I’m an ecologist with a keen interest for coral reefs, so you can bet massive coral death was a relevant – if shocking – topic for a pre-PhD phone chat. My study location had already been hit by not one, but two back-to-back severe cyclones (categories 4 and 5) in the preceding years. Exposed parts of the reef had been stripped bare of corals, but the sheltered lagoon was left untouched. Now, corals in the lagoon were ‘cooking’

My project was supposed to investigate how productive coral reef fish communities can be. But how can you study forest-dwelling birds if your forest was logged and burned, and if most of your trees are now dead or gone?

Embrace change. Seize the opportunity (piece of academic advice continued).

I had to see the reef with my own fascinated eyes. It turns out that corals were gone, but the fishes were still there. What? How? Too many questions. Lucky me, Lizard Island, on the Great Barrier Reef – the very reef smashed by storms and ‘cooked’ by a heatwave – is also one of the best studied bits of the tropical ocean. More than a decade earlier, visionary PhD students (my co-authors) had carried meticulous fish surveys across the reef including exposed and sheltered areas.

In agreement with my supervisor, I outlined a project to repeat their detailed surveys and investigate the impact of coral demise on the energetic dynamics of coral reef fishes. One of the main advances of this research was to investigate acute ecosystem disturbances from the perspective of dynamic, flow-based metrics, rather than static metrics such as abundance. These metrics included productivity, biomass ‘lost’ due to mortality (in reality consumed by predators) and turnover rates.

What we found was counter-intuitive: in the 15 years punctuated by recurring catastrophic events of coral loss, reef fish assemblages became more, not less, productive. This was mainly due to larger, and presumably older, herbivorous fishes, and linked to a massive increase in their favoured food: short algal turfs that quickly colonise dead corals. Yet, we found that rates of biomass ‘recycling’ (i.e., turnover) decreased during this period, likely because large fish grow proportionally less than small ones. Overall, our results cautioned against interpreting the extra productivity following coral loss as necessarily positive, as it may not be stable in the long run if old fish are not replenished.

An interesting aspect of this project is that the field technology used to collect data was, so to speak, quite primitive. No fancy gadgets. Everything was done using measuring tapes, PVC pipes, rusty chains, mosquito nets and the occasional handheld underwater camera. Granted, there was a lot of computational post-processing, but I think it opened up some cool research avenues. For example, what will happen if there is no coral recovery in the next years? Will fish populations be replenished, will they collapse? And what if there is recovery?

We did start seeing some coral regrowth in the last two years, and I was enthused to notice in our latest trip (2021) many relatively small herbivorous fishes swimming about our study site. This is likely a sign of replenishment happened in the three years following data collection for this paper.

After finishing my PhD, I took a post-doctoral position at the Research Hub for Coral Reef Ecosystem Functions at James Cook University, my PhD alma-mater. As a next step, I am working to broaden our understanding of how natural features such as reef structure, ocean currents and seascape configuration, determine how productive can coral reef fish assemblages be and how do habitat degradation and overfishing fit in this. I’m excited to develop and streamline methods to quantify consumer productivity in high-diversity ecosystems. My focus is on coral reef fishes, which are a phenomenal model, but the principles developed should be much more general.

One thought on “Renato Morais: An unexpected (PhD project) journey”