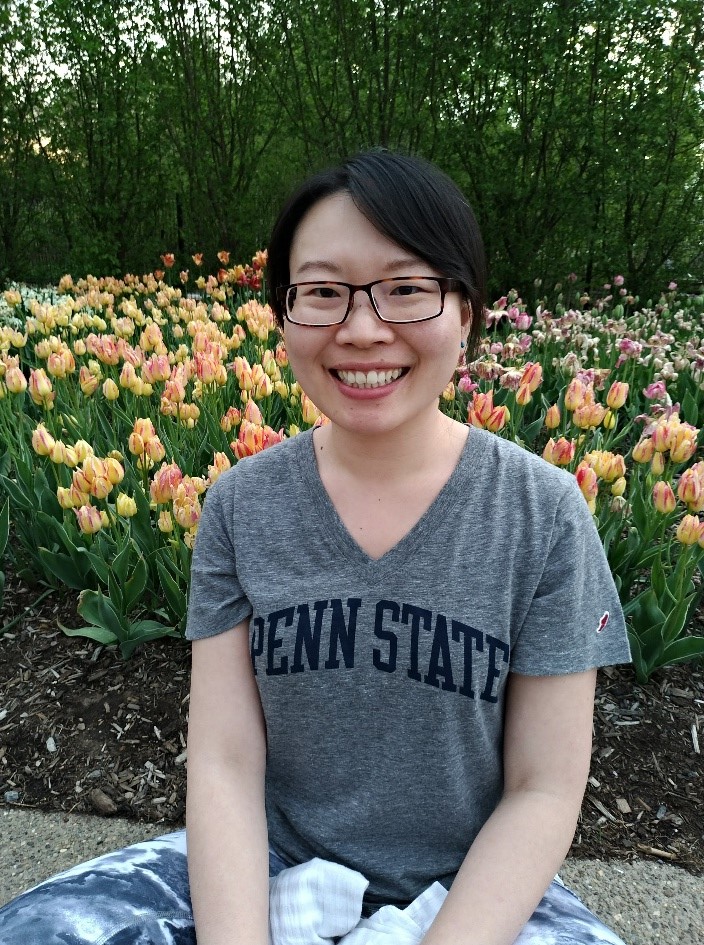

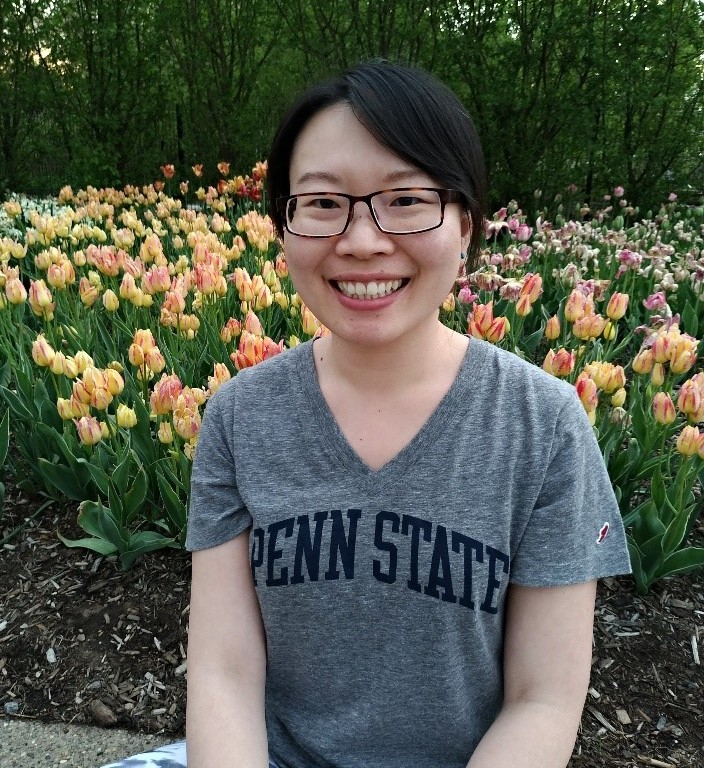

Ching-Wen Tan of Penn State discusses their 2020 Haldane Prize Shortlisted work “Top‐down effects from parasitoids may mediate plant defence and plant fitness” and how patience is the best attitude to have for creativity

How did you get into ecology?

I developed my interest in herbivore-plant interactions from an ecology course as a freshman. After B.S. and M.S. in Entomology, I gained an opportunity to polish my research skills as a technologist in Insect-Plant Interaction lab under the administration of Dr. Shaw-Yi Hwang for five years in Taiwan. My enthusiasm for research helped me obtain the McHenery fellowship offered by The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University for pollination biology studies in Taiwan, USA and The Bahamas. In 2019, I received my Ph.D in Entomology from The Pennsylvania State University, under the supervision of Dr. Gary Felton. Now, I’m in an ecology lab as a postdoctoral researcher under the supervision of Dr. Jared Ali and Dr. Rudolf Schilder at Penn State.

How does your research advance the field?

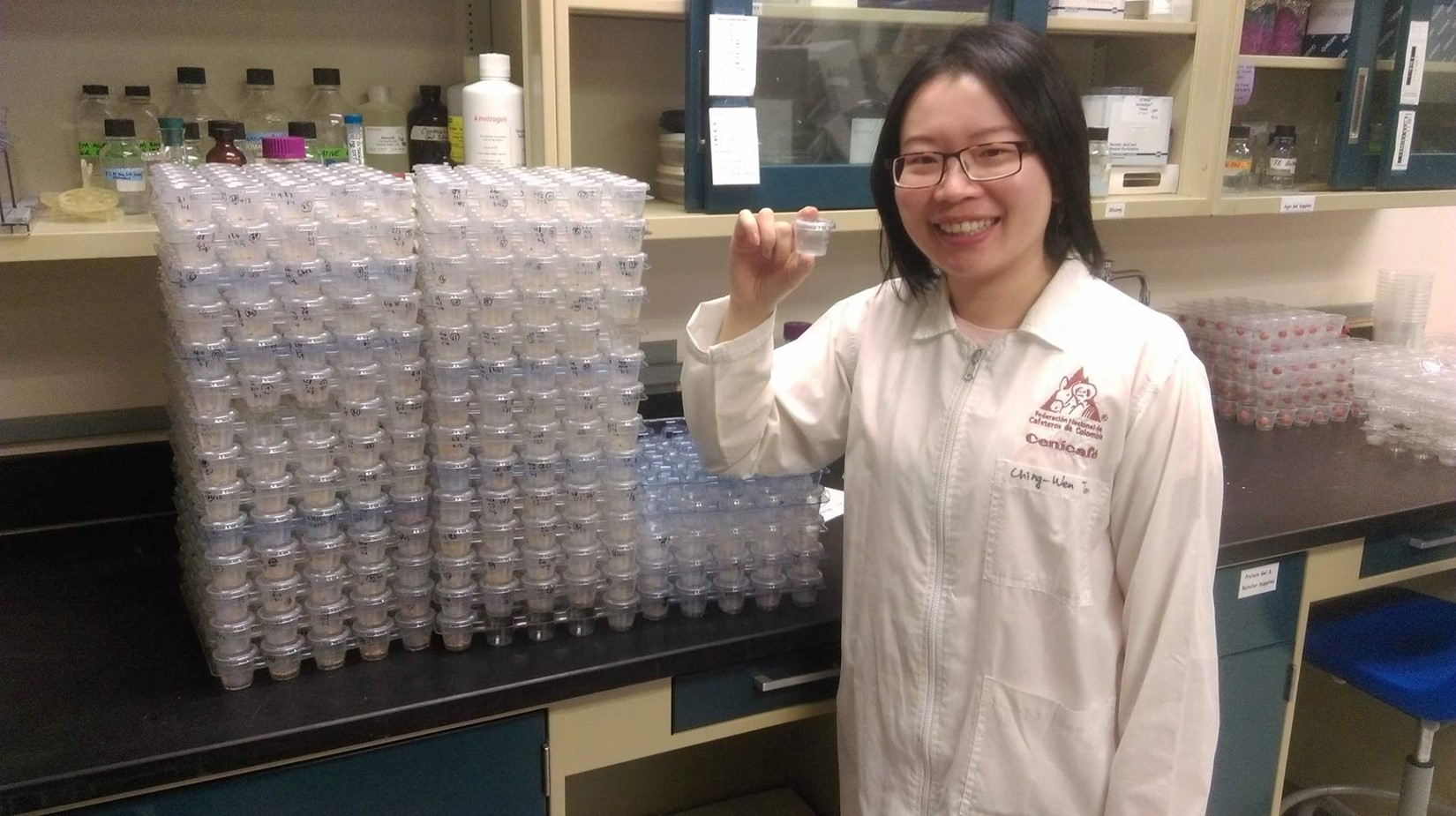

My research focuses on how the third trophic level influences plant perception of herbivorous insect oral cues. Parasitism changes host physiology in order to make the environment suitable to the parasitoid’s offspring. These physiological changes also influence herbivore saliva. In this paper, I focused on saliva changes after parasitism and evaluated how these changes influence plant response to herbivory and plant fitness. Parasitism reduces glucose oxidase activity in corn earworm saliva, which results in lower tomato plant defenses compared to plants that receive saliva from non-parasitized caterpillars. Tomato plants produce higher flower numbers and heavier fruit weight when treated with parasitized caterpillars compared to non-parasitized ones. Moreover, the effects of saliva from parasitized caterpillars also impacts the next plant generation; seeds germinate faster, with higher germination rate when their parental plants were treated with saliva from parasitized caterpillars.

Tomato plant (cv. Microtom) and tomato fruits. Photo credit: Ching-Wen Tan

These results indicate that plants can distinguish between saliva from parasitized and non-parasitized caterpillars and adjust their defenses accordingly. This research highlights never-before-described top-down effects from parasitoids on plant fitness. When considered alongside my previous study, “Symbiotic polydnavirus of a parasite manipulates caterpillar and plant immunity” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy, we can elucidate previously unknown interactions between plants and parasitoids after parasitism. The results of these works reveals a novel aspect of microbe-mediated interactions between plants and insects. The symbiotic polydnavirus (PDVs) not only alters the phenotype of its primary host (parasitoid) and secondary host (caterpillar), but also the host plant of the caterpillar. This is the most extreme example of the known extended phenotype. These contributions demonstrate a remarkable multitrophic effect on fitness: the symbiotic virus has a negative impact on caterpillar fitness but it positively impacts the fitness of its parasitoid host while also positively impacting fitness of the plant.

What did you enjoy the most about this work, and were there any funny experiences?

The thing that I enjoyed most in this project is that every piece of data helps us to reveal previously unknown interactions between multi-trophic levels. This project also brought me lots of opportunities to learn new research skills and collaborate with multidisciplinary groups.

When I was taking care plants for fitness assays, I checked every corner in the greenhouse to make sure there was no way that small animals can get into the space and checked fruits on each plant every day. While I was collecting fruits, I felt that I was like a chipmunk or a squirrel collecting food (tomato) to take to my nest (lab) and store them properly.

I’m still continuing this project and collaborating with young scientists. We would like to know if these phenomena are also showing in the different multitrophic systems.

What is the best thing about being an ecologist?

The best thing to be an ecologist is to enjoy the nature. There are so many amazing things between/among species that can be discovered. Sometimes we have to slow down, be patient and open-minded. You might get unexpected cures/results that boost your ideas. In my spare time I like traveling and crafting.

One thought on “Ching-Wen Tan: The Enemy of my enemy is my friend: beneficial natural enemies indirectly increase plant productivity in surprising new ways”